For thousands of years, Indigenous people on the coast have tended to under-sea gardens — sustainably harvesting clams and other seafood.

“This is something that was a staple for our people for many moons, and life in the ocean was our means where we were able to sustain ourselves by the ocean,” shared Hul’qumi’num Elder Philomena Williams.

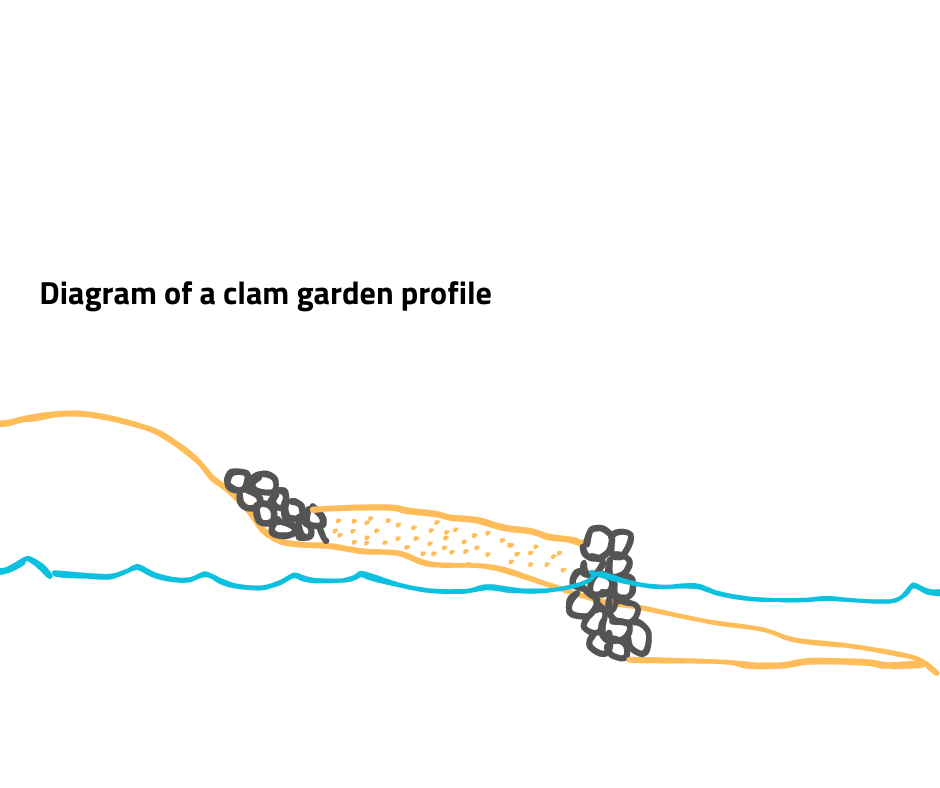

The under-sea gardens work through a simple but effective technology — people move large boulders during low-tide to create a rock wall. These stone walls are built up in inlets and bays, so that when the tide comes in, sediments collect in the intertidal zone Intertidal ZoneThe area of the shore that is exposed to air at low tide and covered with water at high tide. . This area is the space where clams are exposed to the right amount of both water and air that allows them to thrive.

With time, the use of the rock wall expands and deepens the habitat for clams and other shellfish for harvest. As the stone wall continues to be built up, so does the garden.

“That’s going to change the slope of the beach and increase the zone where those butters and littlenecks do really well,” explained Dana Lepofsky, a Simon Fraser University archeologist, in a video about the gardens.

It also changes the drainage, meaning water will warm up and create nutrients, she explained. Those same nutrients feed baby clams and make them grow faster.

Shore

See more →

Clam gardens are built on the shores of inlets and bays, which provide natural protection from strong wave action and turbulent waters, allowing sediments to settle more effectively in the intertidal zone.

Rock wall

See more →

Crafted by moving large boulders during low tide, the walls collect sediments in the intertidal zone, enhancing the habitat for clams and shellfish.

Intertidal zone

See more →

The intertidal zone is the dynamic area along the shoreline that experiences exposure to air during low tide and submersion during high tide.

Rock terrace

See more →

The construction of rock walls in this zone alters the slope of the beach, affecting drainage and temperature, creating optimal conditions for the nurturing of clams.

But since colonization, without regular tending and care, many of these gardens have become dormant.

Still, when the tide is at its lowest, you can still see hand-built rock walls on many beaches from Alaska to Washington State, indicating the remaining evidence of this ancient agriculture system — and meaning the families who traditionally managed them can continue where their ancestors left off.

For the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation on what’s been briefly known as Vancouver Island, harvesting rights to these places have long been held by family units, or ȾEX̱TÁN.

In 2014, people from W̱SÁNEĆ Nation on what’s been briefly known as Vancouver Island entered a partnership with Parks Canada to restore two key clam gardens in their homelands.

The project is now in its second phase, as people from W̱SÁNEĆ continue to ensure their beaches are in good condition and that clam harvesting is sustainable for future generations.

Every part of the process involves utilizing the land — including the way the clams are then cooked in pits in the ground, covered with kelp or fir boughs to steam the shellfish.

This process can be connected back to the W̱SÁNEĆ creation story — their creator is called XÁLS, and this word is contained in the word for digging clams, ḴEXÁLS.

It’s said that when XÁLS was changing people into places, lands and beings, some people did not want to be changed and so they dug holes in the beach to hide themselves.

“The creator overheard them and came to where they were hiding and asked why they were hiding,” according to the W̱SÁNEĆ story.

“They told him that they did not want to be changed. The creator said that if he was to change them, that it was for the good of all people, and then changed them into clams.”

In a short video about the clam garden initiative, W̱SÁNEĆ cultural expert Jim Elliot explained it’s something that’s been important to his people for thousands of years.

“I really believe it’s one of the unique attractions to the coastline for Salish people,” he said.

“All year round you have a very valuable source of protein right at your front door.”

Curious for more science of Indigenous Knowledge Systems?

Explore the solutions for regenerating our planet at Change Reaction.