In this activity, students examine the size and structure of an old growth tree.

Forests are very important for wildlife and humans.

Trees are the lungs of our earth and keep our air fresh—they recycle the carbon dioxide that we breathe out, using it to grow and producing oxygen. The bigger the tree, the more carbon dioxide it removes from the atmosphere and stores in its tissues as it grows. Believe it or not, in one year a single tree can absorb the amount of carbon dioxide produced by a car driven 41,600 kilometres.

Trees also lower air temperature by evaporating water into their leaves. They act as sound barriers against noise pollution, stabilize soil to prevent erosion, and reduce our heating and cooling costs and energy use with their shelter and shade.

A single tree can be the home or habitat for a variety of wildlife, from fungi to insects, from birds to animals. An older and larger tree can be a home for even more creatures, both during its lifespan, and after, as a wildlife tree or standing deadfall.

The Coastal Temperate Rainforest of BC contains trees that are several hundreds of years old and can grow up to 5 metres or more in diameter. These trees make up our old growth forests.

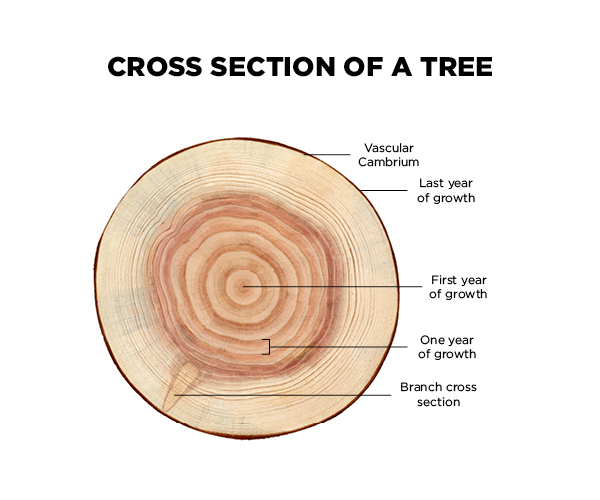

Every year in the growing cycle, a tree adds another ring of growth and slowly expands in diameter. As a tree grows, it adds a light ring of new growth to its trunk during the spring and early summer, when growing quickly, and a thinner, dark ring in the fall, when growth is slower. Scarring on tree rings can even tell the history of fires that burned through a forest.

Scientists can measure the age of a tree by counting all of the rings, starting at the centre and making their way out towards the bark. Because climate affects the amount a tree grows and the thickness of the rings, scientists use tree rings to learn about past climate.

The science of tree rings is called dendrochronology. The use of tree ring records to decode Earth's climate history is called dendroclimatology.

copy.jpg)