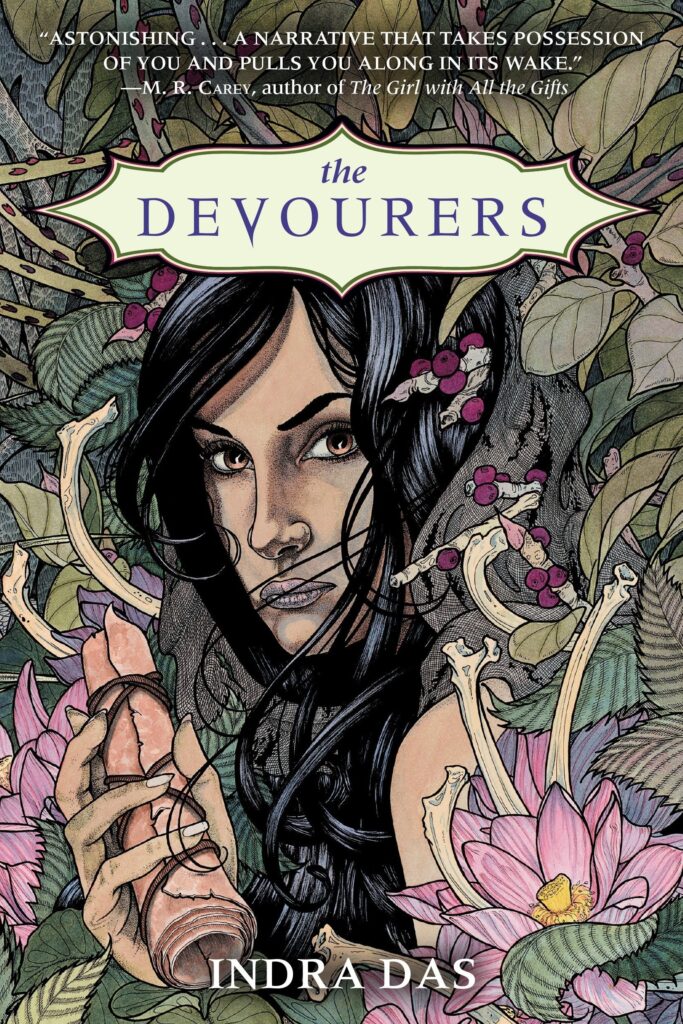

Indra Das is a writer from Kolkata who holds an M.F.A. from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He is a Shirley Jackson Award-winner for his short fiction, and his debut novel The Devourers won the 2017 Lambda Literary Award for Best LGBQT SF/F/Horror. He shares his opinion with Science World.

As a teen, I avoided science fiction in prose despite my love for the same on TV and movies, from Star Trek to Star Wars, from xenomorphs to replicants. Then, I read William Gibson’s Neuromancer in high school, followed by Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash.

Both felt like literary electricity—a jolt to the system, real as any realist novel, and about a space (the Internet) that was affecting reality faster than realist fiction knew how to process.

It’s worth noting that all my early favourites of the genre came from (brilliant, no doubt) white, western writers—the aforementioned cyberpunk classics, Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War, Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed—despite the fact that I was brown and Indian.

Things have changed, a little. Now I, myself, write science fiction that’s globally published, among other things, as do other Indians, as do others beyond the West.

Ideally, science fiction should imagine futures from perspectives around the world and across all demographics.

Just as, ideally, science should be able to work unhindered for the good of all humanity, not just the wealthiest and most powerful nations and populations.

Of course, science does result in miracles, in spite of the way our societies revolve around racial, gendered, and imperial hierarchies.

For a recent example, we might look at the vaccines for the Covid-19 pandemic, countered by global vaccine inequities that have resulted in a failure of coverage.

Similarly, science fiction is not an equal vision of the future, often dominated as it is by western (and white) perspectives.

From Dune to Star Wars, science fiction often ponders empire and the ways in which it fails life, even as those stories are themselves products of the same.

Science fiction is not science. But, it shares an outlook with science—to look ahead into the forbidden (according to Einstein, I think, but I’m not a physicist) country of the future.

It’s unwise to romanticize science fiction as a way to directly affect the future. As LeGuin said, “science fiction is not predictive, it is descriptive.” Some of the world’s wealthiest and powerful people have professed to being inspired by the genre—science fiction is no longer the bullied nerd of global culture.

All the more reason to treat it as art, worthy in and of itself as an incubator of ideas and feelings—and to teach it as art, so that the generations of the future don’t misunderstand the genre as an advertisement for flashy tech and its attendant capital gains.

Since the future is our only temporal destination, we need to approach its impending crises with the ability for empathy and critical thought that art can engender, rather than a ravenous need for ‘progress’ and ‘growth’ with no heed of the consequences.

Science fiction can build essential bridges between science, tech, and the humanities.

Artists, including science fiction writers, are not policy makers, nor social activists, nor scientists (though they can be).

The responsibility of art is not to take up the mantle of other failing systems that are tipping our planet’s ecosystem and societies into taking irrevocable damage. That is the province of science (social and otherwise) and governance.

But art, like science fiction, can and will inspire, entertain, caution, and provide a salve for the fires of the world until they can be controlled, or quenched.

May the fourth be with you.

Follow Indra for more film and literary criticism and explore his work.