Rachel Wang's love for the universe started with, not one, but several big bangs.

"It all started with my parents enabling me at a young age to explode and set things on fire in my backyard," the astronomer at HR MacMillan Space Centre reveals, adding that a book containing 101 science experiments that her mother gifted her was a big source of inspiration.

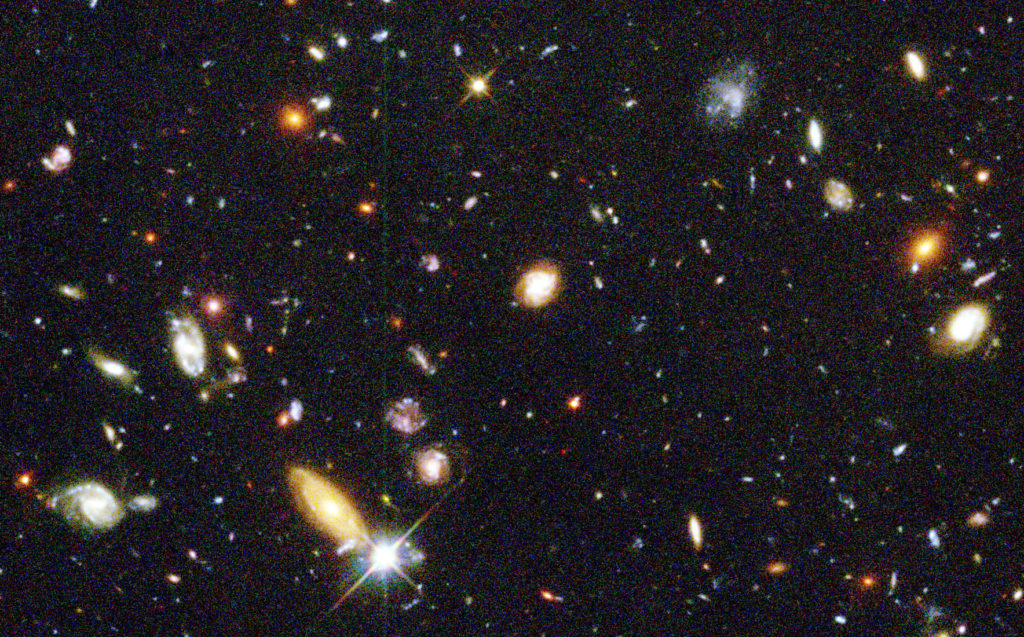

It wasn't long before Rachel’s curiosity turned upwards, and she began to wonder about the far and distant combustions that lit up the night sky.

“I love the fact that there are so many things in space that are absolutely bonkers and unimaginably huge,” she says, joking that there is no shortage of thesis topics on which a curious scientist could embark.

But perhaps equally as abundant are the number of common misconceptions about the way the universe works, which Rachel gets to address on a daily basis at the space centre. How the universe expands, for example, is one of those facts that many find tricky to wrap their heads around.

“Space is expanding from all directions, everywhere — not from a central point. It’s hard to imagine because we know the universe started from a single point, which was the Big Bang,” she says. “But the beginning of the universe is not a point in space that I could give you coordinates for. What we mean by a “single point,” is that it encompassed all the matter and energy we have in our universe.”

One way we can figure out how the age of the universe is by looking at the oldest objects in it. Like a really, really old star.

An Age-Old Question

In 2013, The European Space Agency's Planck spacecraft embarked on a mission to measure the cosmic microwave background, which is the thermal radiation left over by the Big Bang. At 13.8 billion years, Planck’s calculations of the age of the universe closely resembled NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe which, just the year before measured the universe at about 13.7 billion years old.