It's getting hotter in here.

Over the last few decades, we’ve witnessed a significant rise in heatwaves, wildfires, and droughts as a result of centuries-worth of heat trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse gases.

Just this August, British Columbia declared a state of emergency in response to the record-breaking wildfires burning across the province.

Ecologist Christopher Harley and climate scientist Simon Donner — both professors at the University of British Columbia — explain that as temperatures rise up here, they’re also rising in the ocean.

This summer didn’t just break heat records for us here on land, Professor Harley says. It also broke records for marine life.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, we’ve been recording never-before-seen highs for the world’s oceans this year.

In fact, most of global warming is occurring in Earth’s oceans, Professors Donner and Harley explain. Because water absorbs more heat than air, the ocean, which covers about 70 percent of the Earth’s surface, soaks up more heat (about 90 percent!) than the atmosphere.

Scientists say the ocean is a carbon sink because of its ability to draw out carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Well, the ocean is also a heat sink, Professor Harley points out.

What are BC's carbon sinks?

Explore

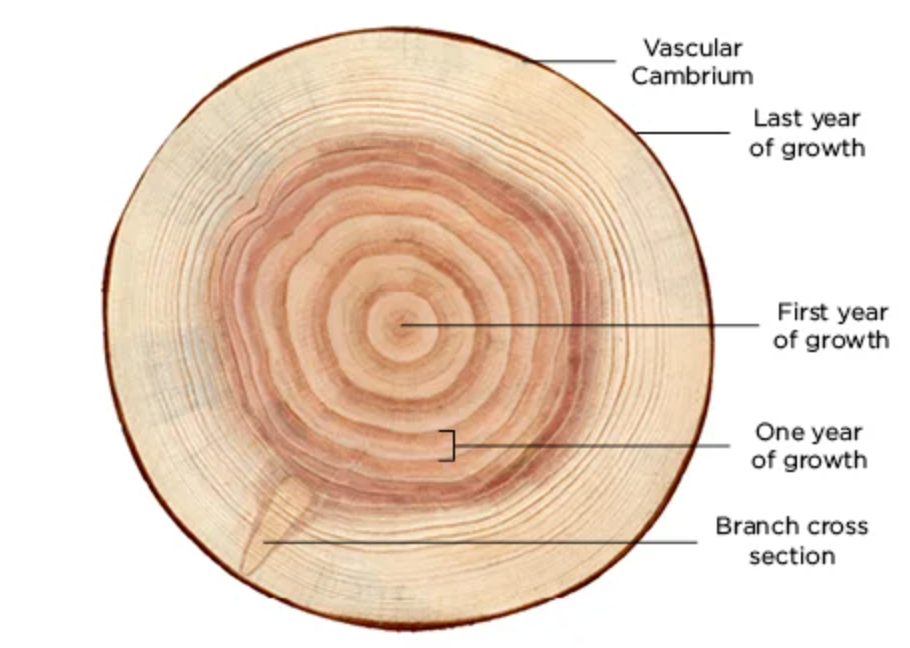

How do trees recycle our carbon?

Look inside a tree

When did BC's marine heatwave start?

Why are coral reefs and kelp forests crucial in rising ocean temperatures?

And just as not every living organism on land is able to seek out cooler conditions during a heatwave, in the ocean, not every marine organism can escape rising temperatures.

On land, a bird might fly to the shady side of a hill when it’s extremely hot outside, but a tree remains stuck in its place, Professor Harley notes. Similarly, during a marine heatwave, some species of fish might be able to swim into deeper, cooler waters but organisms like corals or kelp which often form on top of rocks or other hard surfaces, have nowhere to go.

Many researchers have linked the bleaching of coral reefs and the decline in kelp to a rise in ocean temperatures.

And corals aren’t “just a pretty face,” says Professor Donner. Likewise, kelp isn’t just a leafy organism that billows in the water. Both coral reefs and kelp forests are a home for marine life. They also produce oxygen for the ocean and protect our coastlines from storms.

Professor Donner shares that some scientists — like those at the Kelp Rescue Initiative — are finding ways to restore kelp forests by studying the genetic make-up of kelp species that are naturally more tolerant to heat and running “outplanting” experiments. This means that they propagate and plant these heat-tolerant kelp species in an effort to grow more of them.

“I think there's a lot of promise in that sort of restoration work,” Professor Donner says. “The challenge, to be honest, is that it's hard to do it at a large scale.”

The best large-scale solution is addressing the root cause of vanishing kelp — ocean warming. And to do that, he says we need to do “everything we can to reduce emissions.”

Curious for more science about water and climate change?

Explore the science and solutions for regenerating our planet at Change Reaction.