On Earth, water is everywhere.

It covers more than 70 percent of the planet, it falls from the sky, and it’s even in the ground.

Plants drink it up to grow and thousands (upon thousands upon thousands) of organisms live their whole lives inside of it.

As Simon Donner, a climate scientist and professor at the University of British Columbia points out, "we live on a water planet."

In British Columbia, cascading waterfalls and idyllic fjords are a draw for visitors. And in Vancouver, Douglas Firs, red cedars, and wildflowers prosper under about 170 days of rain each year — a reality we often groan, shake our fists, and mumble "Raincouver!" at.

But in the past years, we've witnessed many manifestations of climate change — from the atmospheric river event that ripped a barge (the infamous English Bay barge) off its anchor onto Sunset Beach to the wildfire that destroyed the village of Lytton and the droughts drying up rivers in BC.

CLIMATE CHANGE IN BC

All these expressions of climate change aren’t separate events, Leah Bendell, a professor of marine ecology and ecotoxicology at Simon Fraser University, says. They’re “connected and have a combined effect on our marine ecosystems.”

Earth won't suddenly stop being a “water planet” and turn into a rocky exoplanet or a gas giant like Jupiter and Saturn where water cannot exist as a liquid.

But, as Professor Donner explains, as sea level rises, so does salty ocean water, and this will affect water quality and availability.

Droughts can have a similar effect. When there's less rainfall, there's less freshwater flowing into the rivers.

As the freshwater level decreases, saltwater from the ocean can start to move inland — a phenomenon known as saltwater intrusion.

Freshwater

See more →

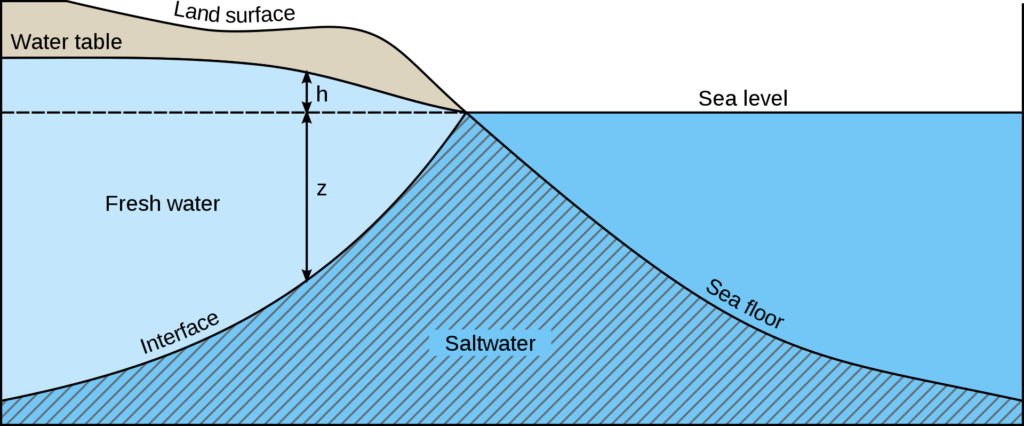

Freshwater typically flows underground toward the ocean and keeps seawater from moving into freshwater aquifers, which allows for safe and potable water (such as the water found in wells).

Interface

See more →

Also called the zone of transition, this area is where saltwater and freshwater mix. Rising sea levels, high tides, and droughts can cause seawater intrusion by pushing the zone of transition closer inland.

Saltwater

See more →

Saltwater flows underground and meets fresh water underground. Saltwater intrusion occurs when ocean saltwater moves inland. This contamination can negatively affect plants, food supply, and drinking water.

Whether caused by droughts or sea level rise, this intrusion contaminates water sources (like wells) with salty water, making it less suitable for drinking, agriculture, and other uses, Professor Donner says.

To prevent saltwater intrusion, barriers such as seawalls or tide gates are often constructed to deter sea level rise.

And, to ensure that communities have access to clean, safe water, water conservation is key.

BC recommends strategies like rainwater harvesting and water reuse. For example, saved rainwater can later be used to hand water vegetable gardens. Some communities also engage in water reclamation — treating wastewater for non-potable uses like landscaping or flushing toilets. By some estimates, reusing shower water to flush the toilet could save 30% of household water. The technology exists, but implementing it is tricky. Learn More

While solutions like these have value, Professor Donner emphasizes that “the real message” is “the more you reduce [global] warming, the less the impacts are going to be.”

Curious for more science about water and climate change?

Explore the science and solutions for regenerating our planet at Change Reaction.