If you went fishing off the coast of British Columbia in the late 19th or early 20th century, you might pull in your bounty to find that you caught halibut, or rockfish, or cod, or herring. You'd likely find that you caught some salmon.

In fact, if you worked in the salmon canning industry, the late 1870s would have been a good time for you.

And, if you fancied yourself a sport fisherperson, then your boat may have been one of thousands crowding the waters of Burrard Inlet or Howe Sound in preparation for the salmon derbies made popular in the 1940s.

For millennia, salmon would hatch and grow in BC rivers (a freshwater habitat) before migrating to the ocean (a saltwater habitat) to spend their adult lives, and then returning to the freshwater they were born in to spawn and continue the life cycle of salmon all over again.

But all over the world, the speed of climate change is advancing.

The weather is becoming too extreme, glaciers are retreating, sea level is rising, droughts are becoming more frequent, and oceans are becoming too acidic and too hot.

The warmer the ocean is, the less oxygen it can hold, and this endangers salmon and other marine life, says Christopher Harley, ecologist and professor at the University of British Columbia.

As our waters get warmer, it will become difficult for salmon to return to the freshwater in which they were born. In place of salmon, fishers might begin to catch more warm-water fish like tuna, he explains.

Reports are already showing a decline in sockeye salmon. Does this mean we won’t be able to eat salmon in the future?

Sockeye Salmon it to me

How Does Salmon Nourish Our Forests?

Explore

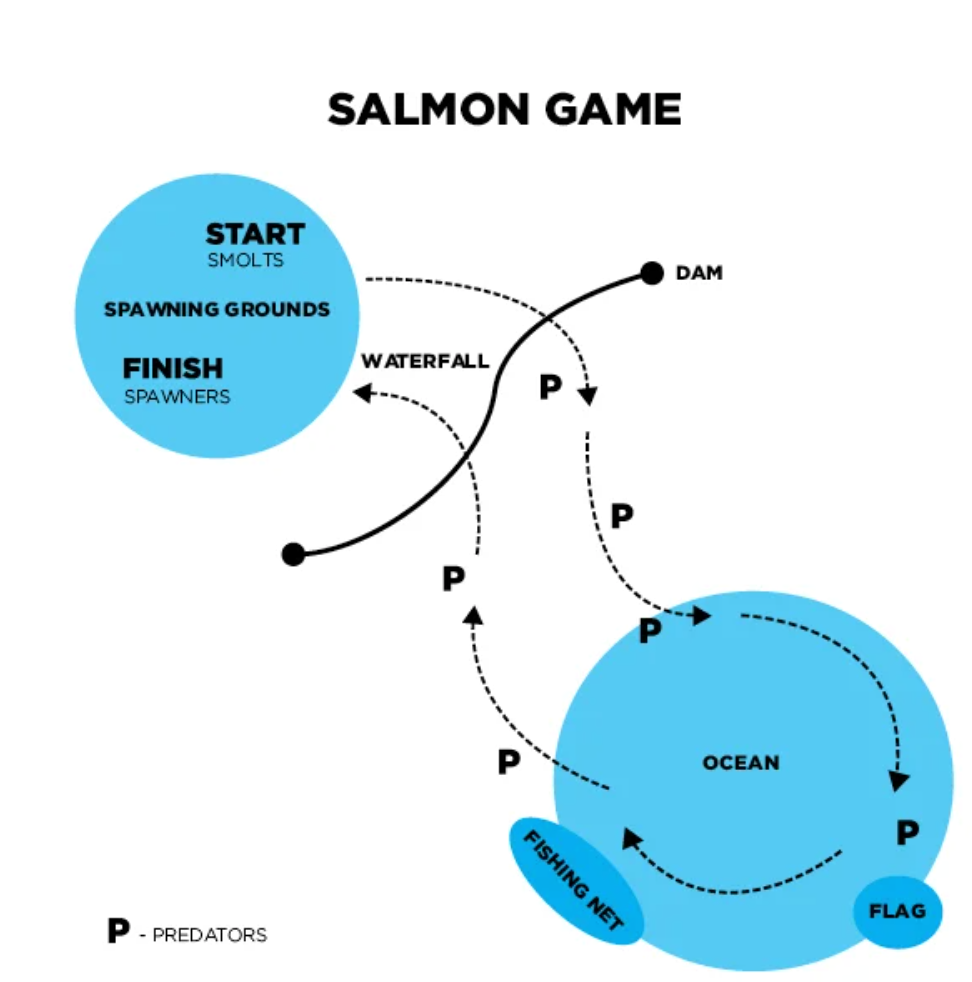

From Fry to Spawners, How Do Salmon Survive in the Wild?

Play this game

Drawn to water and its creatures? Explore the careers of marine biologists.

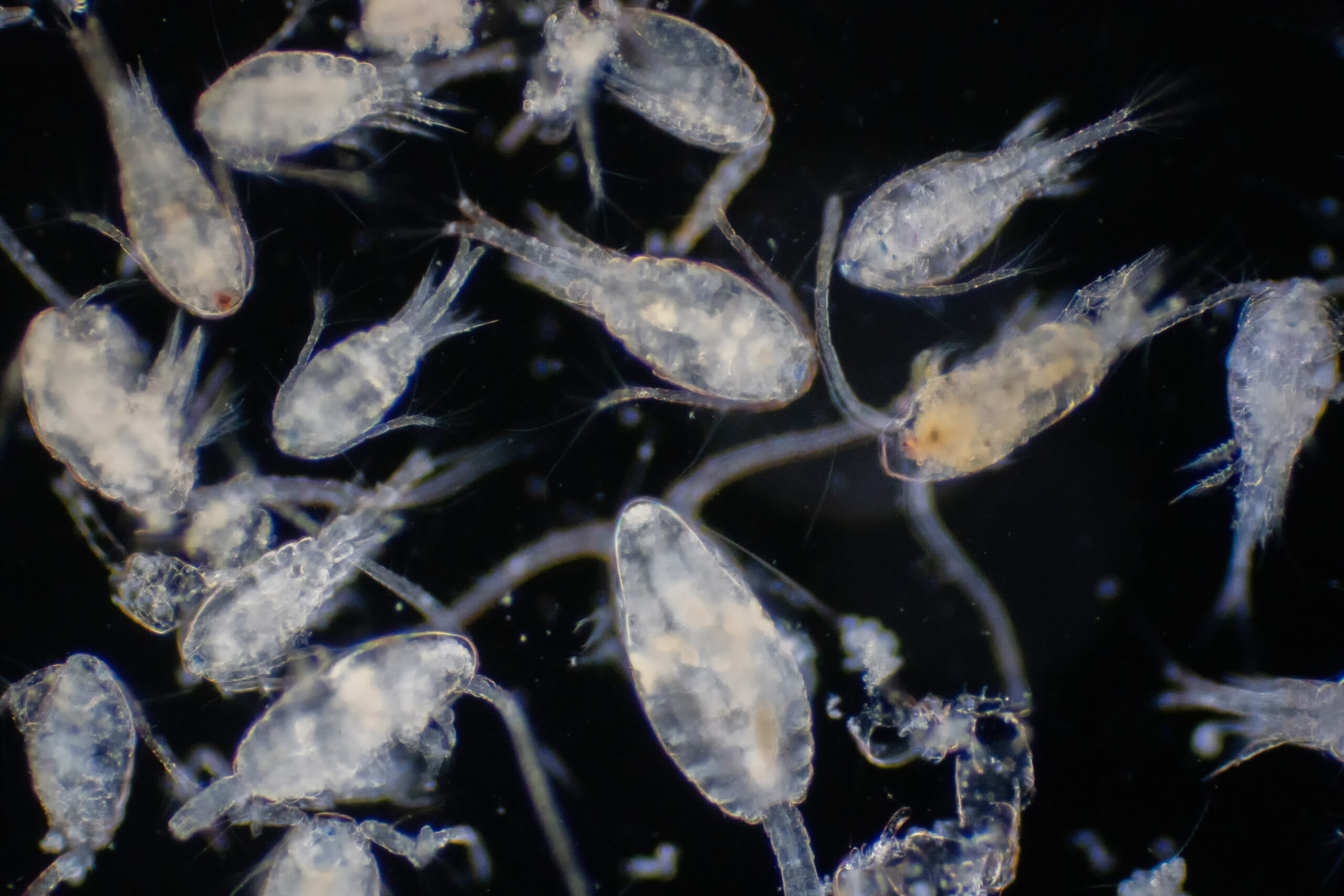

How does oceanic plankton support life on Earth?

Professor Harley says it means salmon will be harder to fish, and as many of our communities depend on salmon for food and income, we could see a rise in food insecurity.

In British Columbia, several organizations are working on improving freshwater conditions, habitat protection, conservation, and restoration.

At the Pacific Salmon Foundation, an online reporting tool helps monitor the effects of drought on salmon (like lower river flow, which can make it difficult for salmon to migrate from the ocean back to their spawning grounds) and encourages people to submit reports on how drought is affecting the salmon populations in their community.

To help salmon survive during droughts, the Foundation also digs deeper pools in areas where they notice the water might be too shallow for salmon to swim, builds temporary shading to deter ocean warming, and installs aerators in rivers to improve oxygen levels AeratorsNature's oxygen boosters in rivers. These devices, installed by environmental experts, infuse oxygen into rivers, ensuring salmon thrive even in the face of drought. .

And at Simon Fraser University's Salmon Watersheds Lab, researchers — in partnership with several First Nations communities and the Nature Trust of British Columbia — are studying several estuaries (an important habitat for young salmon) on Vancouver Island to understand what threats climate change may pose in the coming decades and how best to respond.

“People care enough to act,” Professor Harley says. “And they're coming up with some creative ideas.”

Curious for more science about water and climate change?

Explore the science and solutions for regenerating our planet at Change Reaction.