It's the beginning of the Mesozoic era, the Triassic period. Life on Earth just went through a mass extinction so huge, that 90% of marine groups and 70% of terrestrial groups were wiped out. Dinosaurs then rose to dominance in terrestrial environments, becoming some of the largest and strangest creatures to ever walk the Earth.

The sea, which was once dominated by fish, also became the domain of reptiles.

These fantastic sea creatures have captured the imagination of humans since they were first discovered, with their fearsome and odd appearances. In particular, the plesiosaur, with its long neck and sharp teeth, has inspired countless legends of descendants who could be lost in time and trapped in Loch Ness or Okanagan Lake.

What happened to today's dominant form of marine life—what about fish?

Grazing giants and colossal carnivores

With giant reptiles on the prowl, you'd think that fish had a difficult time surviving in such hostile oceans. But despite losing so much diversity from the mass extinction at the beginning of the Triassic, they bounced back and became diverse through the whole age of dinosaurs.

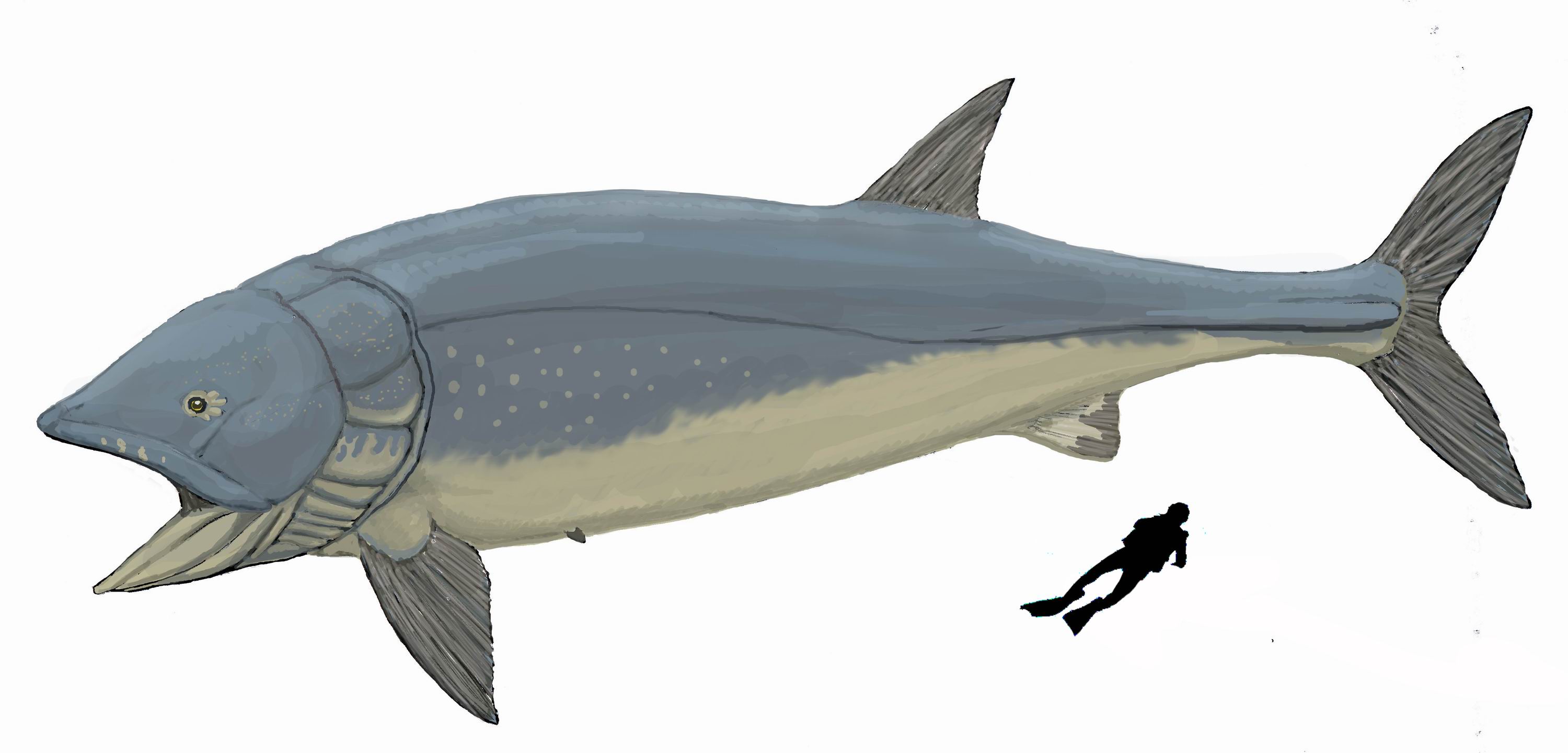

Pachycormids, for example, are fish characterized by partially cartilaginous skeletons and bony plates on their heads. They appeared during the Triassic. One of them, Leedsichthys, was the size of a whale, and fed just like one, filtering the water through its gills and catching tiny floating organisms. Scientists aren't sure how they're related to modern fish—some think that they were early ancestors, others talk of the relationship as distant cousins in divergent evolutionary lines.

Some fish were vicious predators, like ichthyodectids—literally fish biters. Most ichthyodectids ranged from 1 to 5 meters long and were some of the primary hunters of fish in the oceans. They ate by sucking fish into their jaws (like modern bony fish) or grabbing them with unusually big teeth. The largest of these was Xiphactinus—it could reach lengths of 6 meters!

Two huge fish, two different lifestyles. On the top, Leedsichthys, a large filter-feeding pachycormid fish (credit to Dmitry Bogdanov for original image). Below, Xiphactinus, a 20-meter long carnivorous ichthyodectid (credit to Spacini for original photo).

Some of the fish are still around today!

Some ancient groups of modern fish appear in the fossil record during this time, such as the sturgeons, gars and bowfins. Some of these fossils only start appearing as late as the Jurassic, but the characteristics they share with other primitive fish fossils found in deeper layers tells us that they are basal bony fish that have gone unchanged for hundreds of millions of years.

During the latter half of the Mesozoic, fish diversity surged forward. Modern groups like herrings and anchovies, salmon and trout, cod, and all the perch-like fish, appeared between the middle Jurassic and the Cretaceous, eventually becoming prolific in all oceans of the world.

The diversity of sharks

Bony fish aren't the only successful non-reptilian marine animals out there though. Cartilaginous fish, such as sharks and rays, were present during the Triassic, but compared to the Permian period, they kept a fairly low profile for the first 100 or so million years.

Facing stiff competition from the huge marine reptiles that were appearing, the most successful groups were also the most versatile. Hybodonts, or cone-toothed sharks like Hybodus, took it to the next level, with a heavily-ossified skeleton to protect it, a set of teeth that could be used either to catch fish or crush molluscs, and a long dorsal spine to ward off predators. They became incredibly successful around the world, but mysteriously disappeared at the end of the Cretaceous.

Modern sharks, much like modern bony fish, began to appear in the middle of the Jurassic and the beginning of the Cretaceous. As the large marine reptiles waned, they took over their niches and diversified into varied lifestyles and environments. The tooth of a Squalicorax, an ancestral relative of the great white shark, was even found embedded in the leg of a terrestrial dinosaur, suggesting that it was a coastal predator that scavenged on carcasses washed into the ocean when they were available.

Despite their role as apex marine predators, they would sometimes fall prey to dinosaurs as well. Onchopristis (pictured above), a prehistoric sawfish with remarkable similarity to today's species, roamed around North Africa—the stomping grounds of Spinosaurus and Suchomimus, who were well-adapted to hunting down these 8-meter long fish as prize catches.

Overall, fish of all kinds faced low diversity from the Permian-Triassic extinction, and new reptiles dominated the seas they used to rule. Despite these challenges, amazing and diverse forms emerged and went on to become the most numerous and prolific vertebrates on Earth.