Kit Wong-Stevens (KWS): I get quite hot in the summer (laughter), so I'm definitely someone that has always liked to walk under trees.

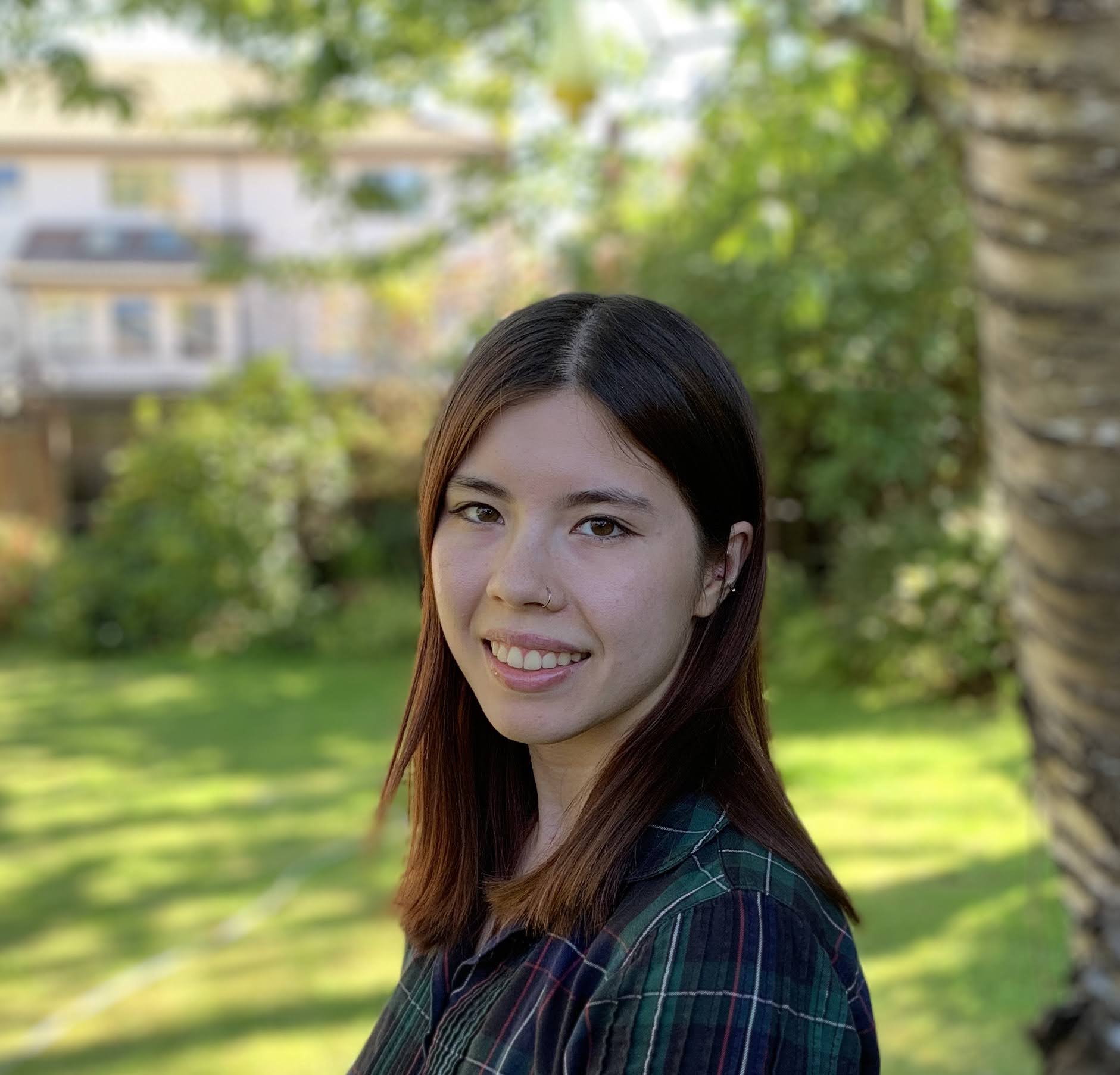

Science World (SW): That's Kit Wong-Stevens. She's a Master of Science student in the Urban Natures Lab at the University of British Columbia. She's researching heat resilience in cities. And at the heart of this work is a deep love for trees.

KWS: One of my favorite trees is the monkey puzzle tree. They’re just these huge trees, they’re kind of spiky, they look like little triangular bits. They kind of do just look like a monkey tail. And the honey locust tree. In the summer and spring, it’s green and then in the fall it turns this very, very pretty golden color.

SW: When she isn’t in the lab, Kit likes to take her friends and family on walks and show them how to identify trees.

KWS: It’s kind of like a choose your own adventure, but for trees. Norway Maples, when you pull a leaf off, when you squeeze the stem, there's a little bit of white sap that comes out and that's how you can tell that it's a Norway Maple as opposed to a Red Maple or a Sugar Maple. Or there's a tulip tree, but the way I like to describe it is it kind of looks as if a kid had decided to draw a tulip.

SW: Early in Kit’s education, she read a study by Christine Carmichael out of Detroit. It challenged the way she thought and felt about trees.

KWS: I remember first reading “The Trouble with Trees,” is the title of the paper, and I was like, “What? What do you mean? What what's wrong with trees? Like, what could possibly be wrong?”

SW: “The Trouble with Trees” looked at the ambitious goal of one non-profit in Detroit to increase the urban tree canopy across the city by planting free street trees. When they received “No Tree Requests” from 24% of residents in a neighborhood, it took a while for them to figure out why.

KWS: There is a lot more that goes into planting trees or deciding to plant trees to benefit people than just planting them. So, people in the neighbourhood had concerns about over-policing in the neighbourhood because there was a history of that. And they were worried about potentially having a lot of concerns about safety and having a lot more tree cover and not being able to see the street as well. There were also a lot of very, very valid concerns about maintenance, since the trees in that neighbourhood historically hadn't been very well-maintained. Concerns about tree location, tree species, pollen, things like that. So that was the first moment I think that opened my mind to that whole social...to the human aspect of the urban forest.

SW: Today at UBC’s Urban Forestry Lab, Kit researches how people in cities connect with green spaces. There’s a strong focus on environmental justice and green equity. The effects of climate change, including this summer's deadly heat dome in western North America, have brought up a lot of questions that need answering.

KWS: Are people using AC? Are people using fans? Are people walking? Are they driving? How are they coping with heat in these different environments? And how do trees play into that? And also how people feel, how it impacts their health and also their ability to access their neighborhood in their city.

SW: A 2018 report by Vancouver's Park Board showed that the hottest neighborhoods in Vancouver have the least tree canopy: Marpole, Southeast Vancouver and the Downtown Eastside. People who live there are at a higher risk of heat-related illness and death, especially heat vulnerable people. Kit’s research focuses on them. They are older adults, pregnant people, young children, disabled people, people with addictions, racialized folks, poor people and unhoused people.

KWS: Do people who are heat vulnerable, do they feel like their environments are hotter? Do they feel in Metro Vancouver that they have a harder time accessing heat-coping resources because they can't afford it? Because it's not near their home? Because they don't feel safe accessing those? If someone is disabled, can they not access trees easily? Focusing a bit more on the equity side of that so that when we're planning for climate change, we're making sure that's equitable.

SW: And Kit knows that a big part of making climate change policy equitable, will be bringing people from all backgrounds into STEM disciplines.

KWS: You know, I think when I was applying to university, on one hand, I was really interested in biology, but I was also you know, very into equity. And I think at the time I was like, “Okay, maybe biology and science,” I felt at the time, “maybe didn't give me the space to kind of explore some of those parts of my identity and get to be as critical and radical and think about those things as some of the more humanities-based majors.” Being LGBTQ in STEM can really help us challenge the way we think about binaries and what science is and what biology is.